Still Resilient

Despite a pandemic, tariffs and superpower political tensions, the resilience of the Chinese economy was clear in 2020. In this issue of Sinology, we highlight five macro trends from 2020 that investors should watch this year.

Despite a pandemic, tariffs and superpower political tensions, the resilience of the Chinese economy was clear in 2020. With COVID-19 largely under control, economic rebalancing towards domestic demand continued, and the Chinese consumer emerged from lockdown, ready to spend. In the fourth quarter of 2020, overall real retail sales and new home sales both rose at faster rates than a year earlier. In this issue of Sinology, we highlight five macro trends from 2020 that investors should watch this year.

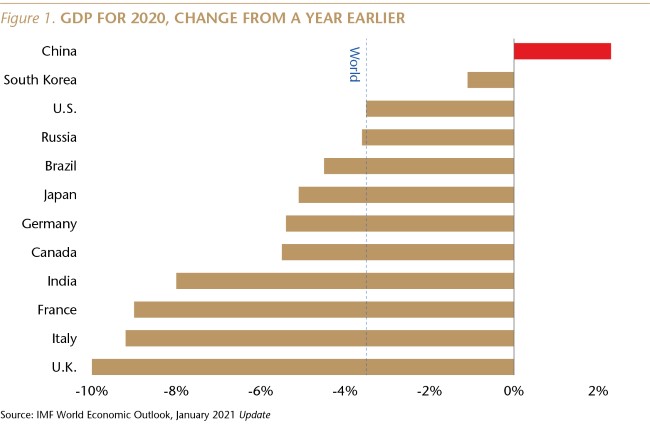

1) China was likely the only major economy to grow in 2020, highlighting the importance of bringing COVID-19 under control.

While the importance of controlling COVID-19 isn’t a surprise, it is surprising how few governments accepted that early, aggressive policies to deal with the pandemic were the best way to save lives and get an economy quickly back towards normal.

I expect an almost immediate, modest improvement in U.S.-China relations, because I expect President Biden to abandon the last administration's approach of treating the Chinese government as an enemy.

In the April 17, 2020 issue of Sinology, we explained that “China appears to have brought COVID-19 under control and laid the foundation for a gradual economic recovery,” and that, “when thinking about prospects for the Chinese economy, one of the most important factors is whether the coronavirus remains under control.”

While the Chinese authorities continue to battle relatively small COVID outbreaks, a year after an initial cover-up and nearly 5,000 deaths, China is one of a handful of countries that have controlled the virus well enough to get economic growth back on track. This is an important lesson as we look ahead to the Biden administration’s more aggressive approach to fighting COVID in the U.S.

As of January 28, there were 1,802 COVID patients in Chinese hospitals, compared to 104, 303 in the U.S. And while China’s population is about four times larger than America’s, there have been only 4,636 COVID deaths in China vs. over 420,000 in the U.S.

This explains why last year, China is likely to have accounted for almost all of global economic growth, as was the case during the global financial crisis (GFC). Over the coming couple of years, this is likely to return to normal, where China will again account for about one-third of global growth, larger than the combined contributions from the U.S., Europe and Japan.

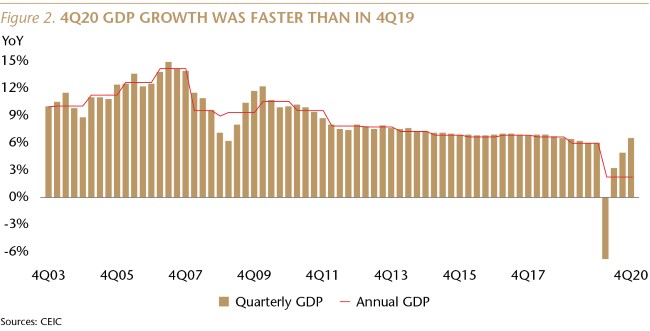

2) As we anticipated, the combination of getting the virus under control and a modest stimulus enabled the Chinese economy to bounce back.

In last April’s Sinology, we wrote that “the most likely scenario is that in the coming quarters China's domestic-demand driven economy will rebound, enabling its economy to put a floor under global growth (as during the GFC) and offer an opportunity to investors.”

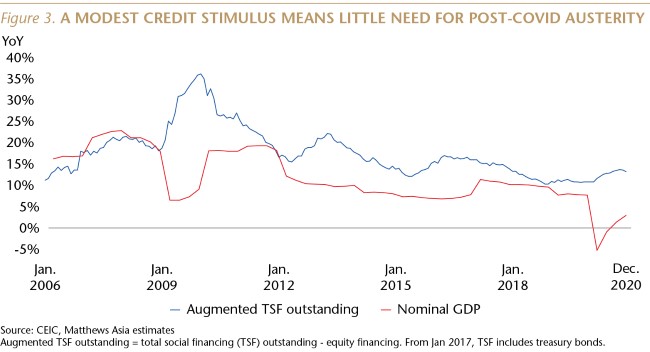

This rebound came with an overall stimulus that was significantly smaller, relative to the size of its GDP, than the U.S. stimulus. For example, China’s aggregate credit (Total Social Finance, or TSF) expanded by 13.3% year-over-year (YoY) by the end of 2020, compared to 10.9% a year earlier, and far from the 36% pace of the 2009 response to the GFC.

Investment in public infrastructure—the Chinese government’s favorite stimulus tool—rose by only 0.9% YoY last year, down from 3.8% growth in 2019 and 19% in 2017.

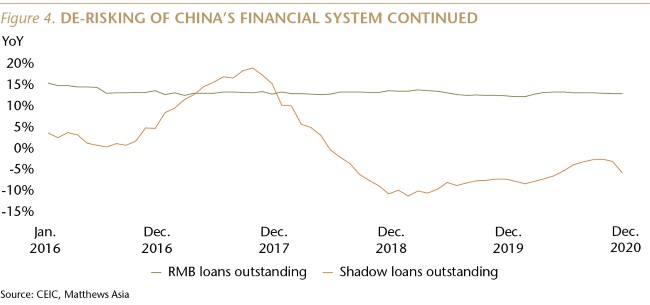

Moreover, despite the impact of COVID, Chinese regulators remained focused on de-risking the financial system. December was the 31st consecutive month in which the YoY change in shadow (off-balance-sheet) lending declined.

The modest scale of the stimulus means that there is no need for significantly tighter monetary policy later this year, when COVID will likely be firmly under control in China. Credit growth is likely to normalize in the coming quarters, but not to the extent that it should disrupt the macro environment, especially in light of last year’s higher base for TSF growth.

3) Despite COVID, China’s economic rebalancing continued.

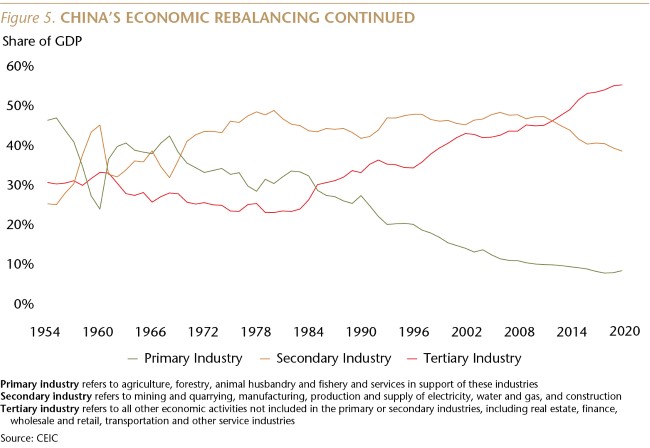

Last year was the ninth consecutive year in which the services and consumption (tertiary) part of China’s economy was larger than the manufacturing and construction (secondary) part, as rebalancing continued despite the pandemic.

Consumption does not yet play as large a role in China’s economy as in most developed countries, but this transformation towards a domestic-demand driven economy is well under way and will continue, offering opportunities to investors.

4) Consumer spending has been improving, and is likely to strengthen further as vaccines are rolled out.

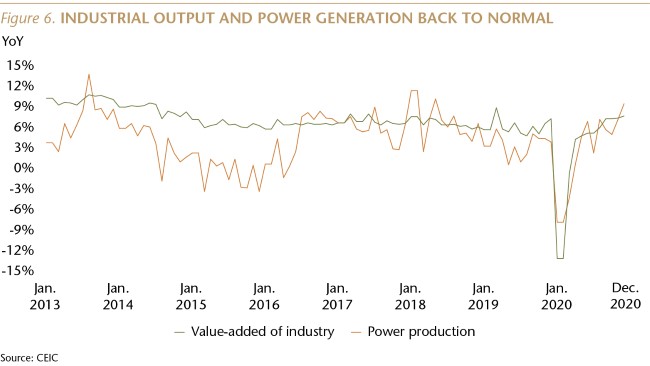

China’s industrial sector fully recovered by the end of last year. In fact, during the second half of 2020, industrial output rose at a faster pace than a year earlier.

But COVID continues to pressure consumption, especially services.

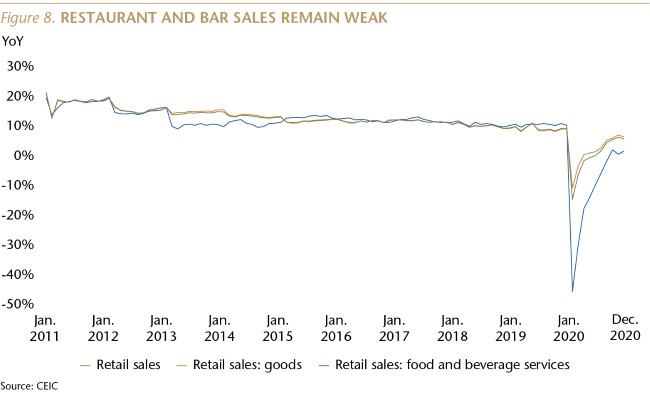

In our April Sinology, we noted that there will be sectoral differences in the economic recovery. “It will take longer for services like restaurants and entertainment to bounce back. Not because the Wang family can't afford to eat out or go to the movies, but because it will take them a while to feel safe from the virus in crowded places.” This is largely how the consumption has recovery unfolded.

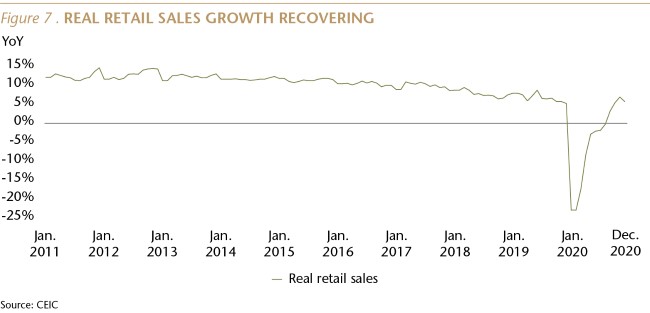

Consumption was relatively weak earlier in 2020, but in the fourth quarter—when COVID was largely under control—there was a significant rebound, and the 5.2% YoY growth rate of real (inflation-adjusted) retail sales in 4Q20 was actually a bit faster than the 4.7% pace of 4Q19.

With COVID fears lingering, however, spending in restaurants and bars remains weak.

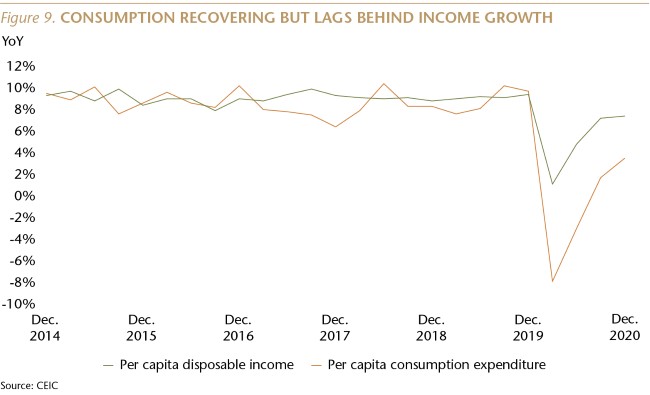

On a broader basis, the recovery in the growth rate of household consumption has lagged behind the recovery in household income growth, reflecting the continuing impact of COVID, especially on services. (In 4Q20, per capita disposable income rose 7.1% YoY, compared to a 9.1% pace a year earlier.)

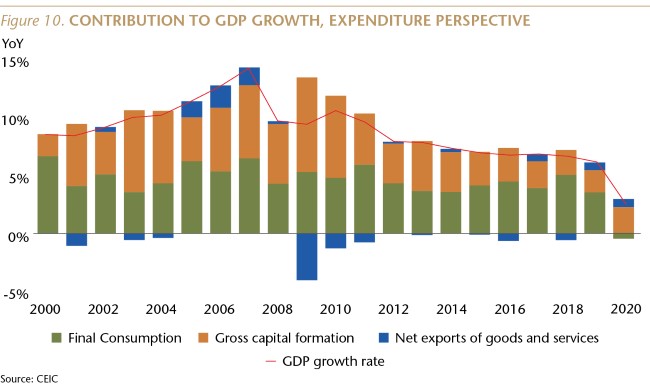

As a result, as illustrated by Figure 10, final consumption contributed negatively to China’s GDP growth for the full year of 2020. That data point has received a lot of attention, but obscures a trend which is more important for investors thinking about 2021: the drag on growth last year from consumption came during the first two quarters, when COVID was at its peak in China. During the third and fourth quarters, with fewer worries about the virus, consumption contributed positively to GDP growth.

The weakest consumption sectors last year were those that rely most on people gathering in crowds: restaurants, bars, entertainment and sports. When widespread vaccinations reduce COVID concerns, those sectors should bounce back.

It is also clear that China’s large middle-class is comfortable spending. For example, new home sales rose 12.7% YoY (in square meter terms) in 4Q20, up from a 2.3% pace a year earlier. And this is far from a bubble, both because buyers must make a cash down payment of at least 20% of the purchase price of a new home, and because the median price for new homes rose 4.2% YoY in December, down from a 6.4% pace a year ago.

With vaccines set to roll out across China, and much of the rest of the world, the consumer recovery is likely to accelerate in the coming quarters.

5) Lower political tensions between Washington and Beijing will reduce political risks for investors.

Putting U.S.–China relations back on a constructive path will be one of the top foreign policy challenges facing the new Biden administration. I expect an almost immediate, modest improvement in the relationship, because I expect President Biden to abandon the last administration's approach of treating the Chinese government as an enemy.

Most importantly, a less confrontational tone from Washington will give Xi Jinping an opportunity to decide if he too wants a collaborative and constructive relationship with the U.S. and its partners. Xi may take the opportunity to recall that the significant changes made by his predecessors who ran China during the decades where the bilateral relationship was characterized by “engagement”—everything from turning over most of the economy to market forces, to granting significant personal freedom to most Chinese citizens—led to a better life for its citizens, a stronger global role for the country, and domestic political support for the Chinese Communist Party.

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist

Matthews Asia