China’s Road to Pragmatism

Despite gloomy news out of China, Andy Rothman explains why he remains optimistic about China’s road ahead.

"Lockdowns are likely to ease next month, and a significant stimulus should follow, designed to promote a second-half economic recovery."

Most of the news coming out of China is gloomy, making it easy to feel pessimistic. I remain optimistic, however, because the main problems are poor, short-term policy choices by the government, rather than deeper, structural issues that are harder to correct. Over the last three decades, Beijing has often made poor choices, but has usually changed course to a more pragmatic path, and I expect that to happen again.

COVID is a mess in China, but a political mess, rather than a public health crisis, so easier to fix. Lockdowns and logistics nightmares meant that there was no macroeconomic joy in the first quarter, and April will be even worse. But, the lockdowns are likely to be eased by next month, and a significant stimulus should follow, designed to jumpstart an economic recovery by the fall. A more pragmatic approach towards Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and the broader relationship with the U.S., is also possible.

I. BEIJING’S POLITICAL COVID PROBLEM

COVID is crushing China. Fortunately, the problem is political and bureaucratic, rather than a public health crisis, so solutions are readily available.

Dozens of cities are under full or partial lockdowns, leaving a population roughly the size of the U.S. stuck at home for several weeks, often with limited access to food and medical care.

The personal impact ranges from boredom and frustration to tragic.

The economic impact is, in the short term, dramatic, with factories and shops closed, and logistics slowed to a crawl in much of the country.

There is, however, room for optimism for three reasons.

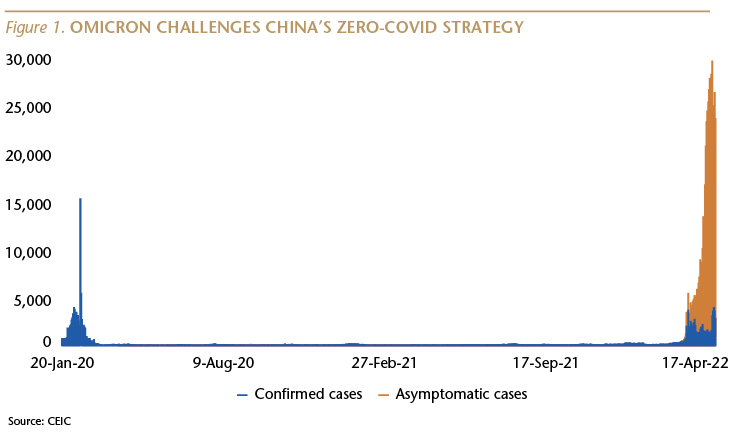

First, because past experience with lockdowns in Shenzhen, Changchun and Hong Kong suggests that the number of new COVID cases in Shanghai—which has recently accounted for over 90% of all cases in China—may peak soon, allowing for the restrictions to be eased. In recent days, there are tentative signs that the number of new cases has in fact peaked.

Second, although the number of COVID cases in China has risen dramatically since late March, the number of cases is not very high, especially relative to the size of China’s population. On April 19, the seven-day rolling average of daily new cases was 24,230 in China, compared to 34,242 in the UK and 33,656 in the U.S., for the most recent dates available.

Third, over 90% of cases in China are asymptomatic, and only 116 cases were considered severe on April 19, meaning that the hospital system is not overwhelmed. There have been only 19 deaths since the appearance of the Omicron variant in China, while the U.S. is reporting a seven-day average of 425 COVID deaths per day.

Given this data, why has the Chinese government opted to respond to the rise in Omicron cases with draconian lockdowns, while most of the rest of the world is lifting its public health restrictions? In my view, the answer is vaccinations.

Beijing Has Not Approved the Use of mRNA Vaccines

The Chinese government appears to be frightened that the very low rate of vaccinations among older people presents too large a risk to living with COVID in the way that most countries are. Additionally, the inactivated whole virus vaccines produced domestically (by Sinovac-CoronaVac and Sinopharm) and used in China are less effective than the mRNA vaccines produced by foreign companies (Pfizer-BioNTech/Comirnaty and Moderna), but Beijing has not approved the mRNA jabs for use in China.

Until recently, the Chinese government’s zero-tolerance for COVID policy worked well. Since the start of the pandemic, China has experienced three COVID deaths per one million population, while the U.S. has seen over 3,000 deaths per million. (To put this into context, Taiwan has had less than 40 deaths per million; New Zealand, Australia, Singapore and Japan all experienced less than 300 deaths per million population.)

The zero-tolerance policy also allowed a healthy level of economic activity. The incremental expansion in the size of China’s nominal GDP last year (an increase of RMB 13 trillion, or about US$ 2 trillion, roughly equal to the size of Italy’s economy) was the largest in the country’s history.

But, the arrival of the Omicron variant exposed two serious weaknesses in China’s approach to vaccines.

Most Chinese are vaccinated, but with vaccines that are significantly less effective than those in use elsewhere. In China, 88% of people have received two doses of the domestic vaccines, one of the highest rates globally. (The comparable rates are 66% for the U.S., 73% for the UK, 75% in Germany, 79% in Vietnam and 91% in Singapore.)

A study conducted in Singapore found that “individuals vaccinated with two doses of inactivated whole virus vaccines [the type produced in China] were observed to have lower protection against COVID-19 infection compared with those vaccinated with mRNA vaccines [produced by Pfizer and Moderna].”

The difference in effectiveness between vaccine types is dramatic for older people who have received only two doses.

China’s Elderly At Risk

A study conducted by researchers at the University of Hong Kong found that for people over the age of 60, two doses of the Chinese CoronaVac vaccine is only 77% effective in preventing death, compared to a 92% effective rate for two doses of the Pfizer vaccine. But, three doses of CoronaVac are equally effective against mortality for older people as three doses of Pfizer (both 98%).

The problem is that in China, only 51% of the total population has had three jabs, and very few elderly people have received boosters.

Why has China not used the more effective mRNA vaccines? The government has not provided an answer to this question, but we can assume it is for nationalistic, political reasons.

Over two years ago, in March 2020, BioNTech announced an agreement with Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical to work jointly on the development of its mRNA vaccine, including collaboration on clinical trials in China. “If approved, Fosun Pharma will commercialize the vaccine in China,” according to a statement by the two companies.

In December 2020, the companies announced an agreement to provide China with an initial supply of 100 million doses of the mRNA vaccine, “subject to regulatory approval,” with initial supply to be delivered from BioNTech’s production facilities in Germany.

3 billion doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine have been shipped to 179 countries, including over 20 million doses which have been used in Hong Kong and Macao—both of which are special administrative regions of China—and in Taiwan, according to Fosun Chairman Wu Yifang.

But the vaccine has not yet been approved for use in mainland China.

Several mainland companies are developing mRNA vaccines, but this doesn’t explain why Beijing has refused to approve the use of the more effective, foreign mRNA jabs, which would mitigate the need for extensive lockdowns and provide better protection for Chinese citizens.

Beijing’s refusal to approve the use of mRNA vaccines is especially risky for China’s older population. There are over 200 million Chinese aged 65 and above (equal to more than 60% of the entire U.S. population), including over 30 million (larger than the total population of Texas) who are 80-plus.

As of March 18, only 51% of those aged 80 and over in China had received two doses, and only 20% had received three jabs. This is likely one of the key factors behind the government’s decision to rely on lockdowns, given the recent experience in Hong Kong.

When Omicron hit Hong Kong, only about 14% of people aged 80 and above had received three jabs, and although that cohort accounted for only 5% of the total population, they represented 48% of COVID hospitalizations and 71% of COVID deaths. Over more than three months, over 8,300 people died of COVID in Hong Kong, accounting for 1.2% of global COVID deaths during that time, while Hong Kong represented less than 0.1% of the world’s population. If China were to experience a similar death rate, that could lead to over 1.5 million COVID deaths in about three months, and China’s hospitals would be overwhelmed.

Contrast the three-jab vaccination rates for China’s elderly population (20%) with those in Japan (88%), South Korea (83%), France (80%), Taiwan (72%) and the U.S. (70%), and it is easy to see why Beijing is resorting to lockdowns. Regrettably, in recent weeks the government has been focused on enforcing lockdowns and conducting large-scale testing, rather than on raising the vaccination rate of the older population. When the lockdowns ease, hopefully Beijing will take the pragmatic path of approving mRNA vaccines and boosting its older population.

II. MACRO WEAK, BUT EASING IS COMING

COVID lockdowns and logistics nightmares meant that there was no macroeconomic joy in the first quarter. And, April will be even worse, given that the lockdowns are even more pervasive this month.

The key for the short-term economic environment is the ending of widespread lockdowns. As noted earlier in this report, past experience with lockdowns suggests that the number of COVID cases is likely to peak soon, allowing for the restrictions to be eased.

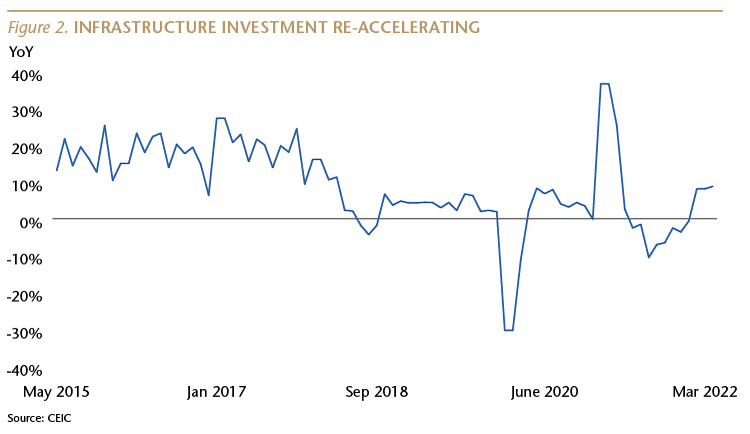

Soon after people are released from home confinement, and allowed to return to factories, offices and shops, I expect the government to initiate a major stimulus program, designed to support a visible economic recovery by the time of the fall Party Congress, when Xi Jinping will formally be awarded a third, five-year term as Party chief. As Premier Li Keqiang said earlier this month, “Policy support needs to intensify at an appropriate time.”

In January, before the widespread lockdowns, I wrote, “I am confident that the easing cycle underway in China will result in stronger economic performance and improved sentiment among Chinese investors, who drive their domestic exchanges.” Given the disastrous economic (and social) impact of the lockdowns, I now expect the government to double down on that planned easing.

Stronger credit flows to corporates and households. More rate cuts, including for mortgages. More government spending, including for public works projects. (In the first quarter, infrastructure investment rose 8.5% year-over-year (YoY), the fastest pace since 2018.) Support for small firms, including loan and rent relief. Possibly direct aid to consumers to jumpstart post-lockdown spending.

It will take time for all of this to get underway, so I don’t expect to see a visible recovery until the second half of this year.

Resi Recovery Likely in Second Half

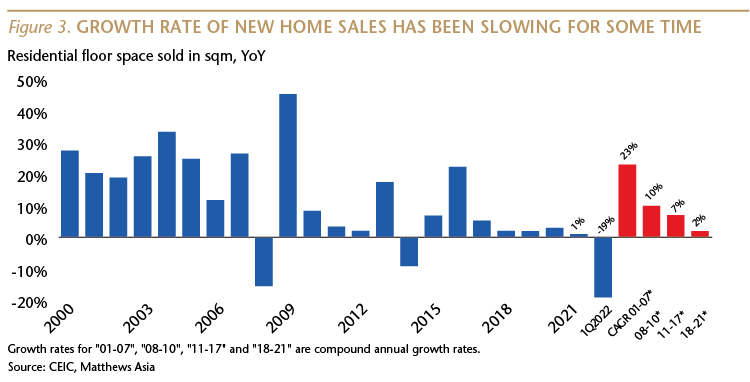

I am also optimistic that China’s residential property market will begin to bounce back in the second half of the year.

My optimism is grounded in evidence of strong fundamentals and of policy easing.

The fundamentals include that most new home sales are to owner-occupiers, and buyers are required to put down a lot of cash. Chinese homebuyers who use a mortgage must put down at least 20% cash for a primary residence (and much more for an investment property), in sharp contrast to the 2% median cash down payment in the U.S. in 2006, prior to our housing crisis.

Prices have remained healthy, rising roughly in line with income growth through last year. Over the last five years, home prices rose at an average annual pace of 7.7%, while per capita urban household income rose at an average annual rate of 7.1%. Over the last 10 years, home prices increased at an average annual rate of 7.6%, compared to average annual income growth of 8.1%.

The market weakness that began last year was caused by government policy, not soft demand. In a misguided effort to stress the market and promote the takeover of weaker, riskier developers, last May, the government instructed banks to severely limit issuance of mortgage loans to homebuyers. As a result, after rising 39% YoY during the first five months of 2021, new home sales (on a square meter basis) declined 13% YoY during the following seven months.

This led 16 developers, which together accounted for 12% of new home sales by volume last year, to default on debt obligations.

Government officials have acknowledged that they put too much pressure on the property market and have signaled that they will take a less restrictive approach this year. Mortgage availability has improved and rates have been reduced. In many cities, the cash down payment ratio has been cut, although no lower than 20%. The central government has permitted local officials to take other steps to promote sales, including relaxing home purchase restrictions and increasing access to home provident loan funds.

There is plenty of pent-up demand that wasn’t met during the last three quarters, so—assuming the widespread COVID lockdowns end soon—the growth rate of sales and prices is likely to recover by mid-year.

Inflation Not an Easing Obstacle in China

The consumer price index (CPI) is rising in China, but not nearly enough to make the central bank nervous about easing. In the first quarter, China’s CPI rose at a healthy 1.1% pace, compared to 8% in the U.S. This follows the 2021 experience, when CPI rose 0.9% in China and 4.7% in the U.S.

Rising global oil prices have had much less impact on CPI in China, because energy is a smaller share of the consumer basket, and because when global oil prices rise, the Chinese government has a mechanism in place which forces state-run oil companies to absorb some of the increase above a certain level, rather than pass it on to consumers.

This month’s lockdowns are likely to lead to temporarily higher food prices, but I do not expect CPI to rise to a level high enough to interfere with the Chinese central bank’s plans to further cut interest rates and boost credit availability, at a time when the Fed plans to keep raising rates in the U.S.

III. PRAGMATIC REASONS FOR OPTIMISM

Most of the news coming out of China is gloomy, making it easy to feel pessimistic. I remain optimistic, however, because the main problems are poor, short-term policy choices by the government, rather than deeper, structural issues that are harder to correct. Over the last three decades, Beijing has made many poor choices, usually driven by misguided political factors. But, the government has usually changed course to a more pragmatic path, and I expect that to happen again.

It's worth remembering that the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, including under Xi Jinping, has succeeded when it has been pragmatic.

When I first visited China as a student, in 1980, its per capita GDP was less than that of Afghanistan, Haiti and Bangladesh, and 80% of China’s population was living below the World Bank’s poverty line. Today, Chinese consumers are estimated to account for 20% of global luxury sales.

In the 10 years through 2019, China, on average, accounted for about one-third of global economic growth, larger than the combined share of global growth from the U.S., Europe and Japan. In 2020, China was the only major economy to register growth.

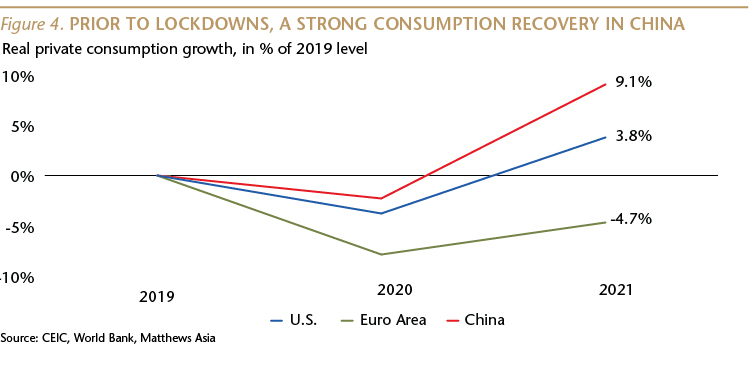

Last year, the COVID-era recovery in inflation-adjusted (real) private consumption was greater in China, compared to 2019 levels, than in the U.S. and the Euro Area.

This was all the result of pragmatic policies that emphasized market-based reforms and de-emphasized the economic role of the state. When I returned to China in 1984 as a junior American diplomat, there were no private companies—everyone worked for the state. Today, almost 90% of urban employment is in small, privately owned, entrepreneurial firms. With the state-sector continuing to shrink, all of the net, new job creation comes from private companies.

Some foreign observers have argued that under Xi Jinping, the Party has rolled back those reforms and has favored state-owned enterprises (SOEs), but the data does not support that theory. The share of employment and of exports accounted for by privately owned companies has continued to rise, and last year was the 10th consecutive year in which the services and consumption (tertiary) part of GDP was larger than the manufacturing and construction (secondary) part.

A new study by the Peterson Institute for International Economics found that “the Xi Jinping era so far, taken as a whole, has been a time of unprecedented displacement of state firms away from the top ranks of China’s corporate world.” The study notes that the share of private firms in the market cap of China’s top 100 listed companies has risen from single digits to about half of the total during Xi’s tenure as head of the Party. SOEs, the study concludes, “are gradually losing their previously uncontested hold on China’s top corporate slots.”

Some investors have been concerned that last year’s regulatory crackdown was an effort to roll back China’s private sector, but in a recent issue of Sinology, I explained why that is unlikely. In my view, Xi is attempting to address the same socio-economic concerns that most democracies are wrestling with, although initial implementation has been chaotic. If the regulatory process is improved, and Xi succeeds in reducing inequality and strengthening corporate competition, he could lay a foundation for the next phase of China’s market-based development. If he fails, it would be because of poor implementation of policies designed to create “common prosperity,” not because he is anti-entrepreneur. We’ve already seen some negative consequences of poor implementation, but I expect these to be improved in the coming quarters.

Recently, we’ve seen some evidence of a return to pragmatism by Beijing. For example, negotiations between the Chinese and American governments on a process for the U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to inspect the audit workbooks of accounting firms in China working for Chinese companies listed in New York had been deadlocked for many years. With a deadline approaching that could lead to the delisting of all Chinese companies from U.S. markets, Beijing last month announced it is now willing to accept the same PCAOB inspection process that has been in place in 25 other countries. I expect the PCAOB to undertake several trial inspections of Chinese accounting firm workbooks in the coming months, and, if those go smoothly, a deal to avoid delisting should be announced by the end of the year.

A second example of pragmatism was the February approval for the use in China of Pfizer’s Paxlovid pill for the treatment of COVID, the first approval by Beijing of a foreign drug or vaccine for COVID. Hopefully, this lays the foundation for Beijing to approve the foreign-developed mRNA vaccines as well.

Foreign Policy Pragmatism Is Equally Important

In addition to returning to pragmatism in economics and public health policy, it is important for Beijing to re-embrace foreign policy pragmatism.

Yuen Yuen Ang, a professor of political science at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote in the March issue of Noema magazine that, “The world does not need China to be great—but only to be pragmatic again.”

Ang explains, “China’s rise under Deng Xiaoping is not a validation of the strengths of authoritarianism over democracy—rather, it represents the triumph of pragmatism. Pragmatists value peace and prosperity as the ends and to do whatever is necessary to achieve them, even if it entails breaking ties with friends and working with rivals. To be ideological means to regard opposing enemies as an end, even if fighting comes at the price of peace and prosperity.”

“To be sure, Chinese leaders and officials have never formally endorsed Russia’s attack, but they have also refused to criticize it,” Ang wrote. “But this pretense of neutrality is impossible to maintain as Putin’s army continues to shell and kill civilians in Ukraine—in clear violation of China’s long-standing insistence on respecting territorial sovereignty.”

(On April 14, U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan “indicated that so far he had seen no evidence that China was stepping in to help Mr. Putin with either military or financial aid,” according to the New York Times.)

Professor Ang writes that, “To avoid the return of a Soviet-era-style Cold War and for global peace to reign, Beijing must once again embrace pragmatism over ideology. . . To turn the current dangerous situation around, Beijing should play the part of a constructive peacemaker not just in words, but in action. . . . For China, the moment to positively change how the world sees it is now.”

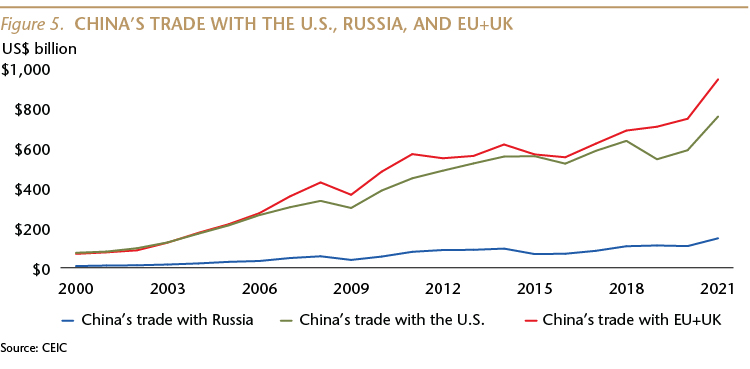

Certainly, the economics aspect of China’s relationship with Russia calls for a very different, more pragmatic approach to the invasion of Ukraine.

Professor Ang concludes her article with an important suggestion for Washington:

“It takes two hands to clap. The Biden administration should also realize that framing U.S.-China competition as a moral contest between democracy and autocracy sets up expectations in Beijing that the U.S. is bent on having an ideology-based Cold War, which gives Xi little desire to work at averting one. As much as hawks in Washington see China as an existential threat, Xi’s leadership sees them the same way, which explains their hard line.

Robert McNamara, former U.S. Secretary of Defense, underscored a core lesson in foreign policy: “empathize with your enemy.” President Kennedy averted a nuclear catastrophe during the Cuban Missile Crisis because he was willing to think from Khrushchev’s perspective. “We must try to put ourselves inside their skin and look at us through their eyes,” McNamara advised.

Saving the world calls for pragmatism in Beijing and empathy in Washington.”

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist

Matthews Asia

As of March 31, 2022, portfolios managed by Matthews Asia did not hold positions in Sinovac Biotech Ltd., China National Pharmaceutical Company (commonly referred to as Sinopharm), Pfizer Inc., Moderna Inc., or Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. As of March 31, 2022, accounts managed by Matthews Asia portfolios held positions in China National Accord (which is owned by Sinopharm).