China Tariffs in Perspective

It’s not U.S. tariffs we need to be fixated on to gauge China’s economic growth trajectory but the ability of its leadership to rebuild confidence among entrepreneurs and consumers.

We are all so focused on Donald Trump’s next tariff move on China that we risk losing sight of the fact that it is Xi Jinping’s decisions on domestic economic policies that are the more important factors for investors. Domestic demand is, after all, the main driver of China’s economic growth and it’s up to Xi to fix the key problem: his country’s entrepreneurs and consumers have lost confidence.

Xi has been increasingly supportive of China’s private sector in recent months and his messaging to technology leaders earlier this month was significant. I believe he will eventually adjust both his rhetoric and policies so that they rebuild trust and confidence. When confidence in the economy does return, investment and spending by Chinese entrepreneurs and consumers will be supported by the massive increase in savings since the start of the pandemic.

Exports Aren’t the Future—Domestic Demand Is

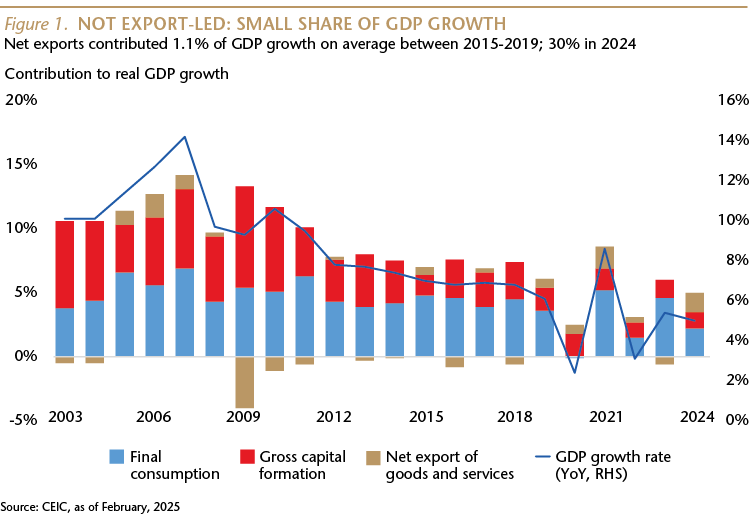

China’s domestic demand is far more important than its exports because exports are a relatively small part of China’s GDP. The net export* share of China’s nominal GDP peaked at 8.5% in 2007, and dropped to 1.7% in 2017, before the first round of Trump tariffs. In 2023 (the most recent data available), net exports accounted for 2.1% of China’s GDP, compared with 4% in Germany, -1.5% in Japan, and -2.9% in the U.S.1

Another way to look at it is that in the five years before COVID, net exports accounted for an average of 1.1% of China’s annual real GDP growth**. This share has been more volatile recently due to global supply chain disruptions and slower domestic demand at home. In 2023, net exports were a -11% drag on growth with 86% of growth coming from domestic consumption. Last year, however, consumption slowed and net exports contributed 30% of China’s GDP growth.1

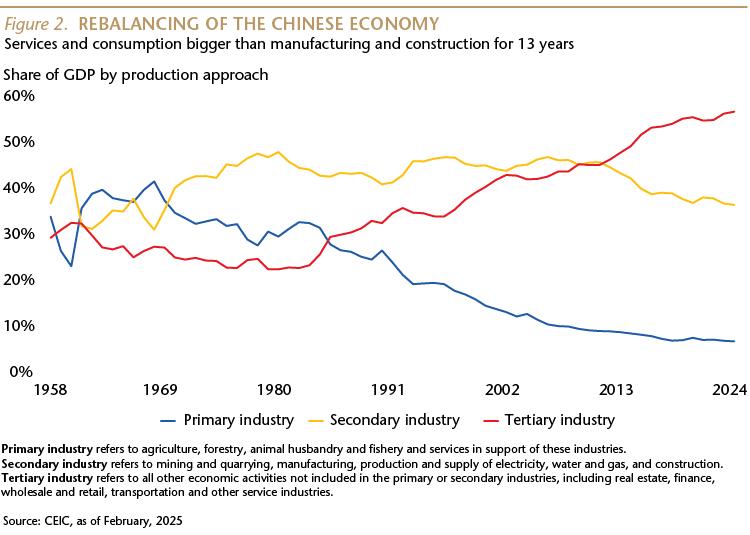

Exports aren’t the future for China. It already has the largest share of global exports and manufacturing and there is increasing political concern in many countries about this dominance. So there are multiple pressures for China’s future growth to be sourced domestically and there is clearly a base for this. China has the world’s second largest and fastest-growing consumer market. It is also an economy in a transition that is well underway. In 2024, 57% of China’s GDP was in tertiary activities, which includes services and real estate, while the share of manufacturing and construction fell to 36% last year from 47% in in 2006.1

Demand Is Weak but Not Collapsing

Hopefully Xi Jinping is spending more time worrying about weak domestic demand than he is about Trump’s next tariff plans. It is, however, important to recognize that China’s economy is weak rather than being on the verge of collapse. The residential property market is a good example of weakness. Sales of new homes, on a square meter basis, fell 14% YoY last year and were 42% below 2021. Sales at China’s bars and restaurants rose 5% YoY last year, down from a 9% YoY growth rate in pre-COVID 2019.1

On the other hand, some of last year’s macro data was encouraging. Per capita household income rose 5% YoY and electricity consumption, a good proxy for industrial activity, rose almost 7% YoY and was 35% higher than in 2019.1 And looking ahead, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts China will have the second-fastest GDP growth rate (after India) of all major economies this year and next. This pace will see China account for about 20% of global growth, a larger share of global growth than from the G-7 countries combined.

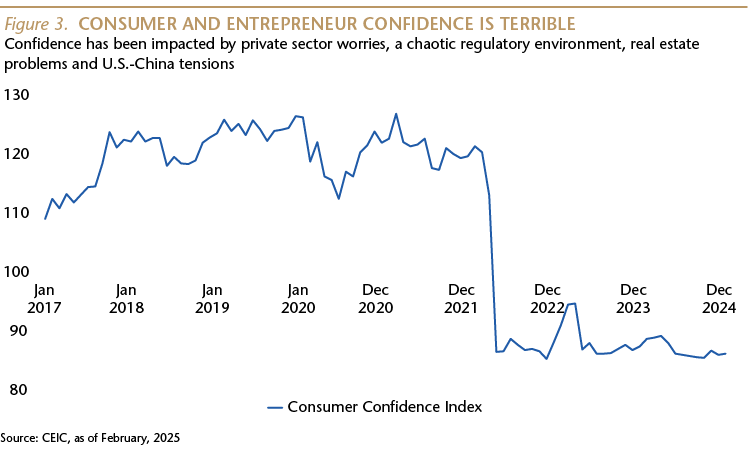

This projected growth rate, however, is not adequate for China’s workers and companies. And it is far from exciting for global investors despite low equity valuations. The catalyst for stronger growth is missing. The main problem, in my view, has been a collapse in confidence among China’s entrepreneurs and consumers.

Confidence among entrepreneurs has been weak for several years because of doubts about Xi’s support for private companies, tensions in the U.S.-China relationship and, most importantly, because of a series of chaotic regulatory policy changes which upended many sectors.

Confidence Is key

Confidence among entrepreneurs is critical as they are the engine of China’s economic growth, the reason China has become wealthy and the reason the Chinese Communist Party has remained in power for so long. Xi must recognize this because he worked in some of China’s most entrepreneurial places during his long career and his late father, Xi Zhongxun, oversaw the early market-oriented reforms in Guangdong from 1978 to 1980. Back in 1984, when I worked in China as a junior American diplomat, there were no private companies—everyone worked for the state. Today, almost 90% of urban employment is in small, privately owned, entrepreneurial firms.

The rise of China's private sector has continued under Xi. Since he became head of the Party in 2012, private firms have continued to drive all net, new job creation. Official media report that the private sector accounts for more than half of China’s tax revenue and more than 60% of its GDP.2 Trade, too, is dominated by entrepreneurs. In 2024, private firms accounted for 64% of the value of exports, up from a 38% share in 2012 and only 7% in 2001.1

Xi has recently promoted an economic strategy focused on “new-quality productive forces,” which will rely on the success of China’s entrepreneurs. This strategy, Xi has said, depends on “disruptive technology . . . to give birth to new industries. . . that are characterized by high technology, high performance and high quality.”

To achieve his objectives, Xi has to rebuild confidence in the private sector which, according to officials, represents over 90% of China’s high-tech companies. By our count, 13 of the 15 globally significant Chinese battery makers are privately owned; seven of the top 10 electric vehicle makers (by number of units produced), are privately owned; and all of the eight leading artificial intelligence (AI) startups are privately owned.

It's also important to keep in mind that because the majority of urban consumers are either entrepreneurs or employees of small, privately owned firms, restoring confidence among private companies—so that they invest in and hire for their businesses, which will lead to job and wage growth—is also critical to rebuilding consumer confidence and spending.

Consumer confidence was relatively resilient during the regulatory chaos but collapsed during the 2022 Shanghai COVID lockdown. More than two years after that lockdown and other zero-COVID policies were ended, consumer confidence—as measured by the Chinese government’s own survey—remains at historically low levels.

What Can Xi Do?

In recent years, Xi has announced a series of policies intended to address the same socio-economic concerns that most democracies are wrestling with, from income inequality to unequal access to education and health care, and housing affordability. Unfortunately, implementation of these policies was often poorly managed. Policy objectives were not accomplished, and unintended consequences damaged commercial activities and entrepreneurial confidence.

“Xi may be trying to refute the view held by some that recent regulatory obstacles faced by entrepreneurs had an ideological origin.”

Last year, many of those disruptive policies were reversed, sometimes quietly, sometimes partially. Some sectors are recovering, like online gaming and e-commerce. Real estate, a major component of the domestic economy, has stabilized a bit but is at a very weak level.

Xi has said he wants to “enhance the ability to get rich,” and that “small and medium-sized business owners and self-employed businesses are important groups for starting a business and getting rich.” He’s also said, “It is necessary to protect property rights and intellectual property rights, and protect legal wealth.”

Xi now needs to persuade his nation of entrepreneurs that he is serious about those objectives. I therefore expect him to follow in the pragmatic footsteps of his predecessors. In 1992, China’s economy was in far worse shape than today, with high inflation and unemployment. Deng Xiaoping embarked on a tour across southern China to promote the country’s nascent private sector, stating that “Whoever is against reform must leave office.” His rhetoric and policies were persuasive enough to kick off a two-decade growth boom, with average annual double-digit GDP growth.

Xi needs to make his own version of Deng’s famous 1992 southern tour, providing rhetorical support for entrepreneurs, promising (and delivering) a more transparent regulatory environment for private firms, and restoring credit lines to healthy developers.

When Will Xi Do It?

During the second half of last year, Xi increasingly moved back toward policy pragmatism. But he did not move far enough to restore confidence. In my view, Xi will eventually feel under growing pressure to overcome his stubbornness—as he did with zero-COVID and property—and adjust his rhetoric and policies to rebuild trust among China’s small businesses and consumers. He will, at some point, make the changes that are necessary to achieve his economic objectives, which are central to his broader goals for his nation.

A February 17 speech by Xi to China’s leading entrepreneurs may be the confidence-restoring step we’ve been waiting for to revitalize domestic demand. Addressing an audience which included Alibaba’s Jack Ma, as well as leaders of DeepSeek, CATL, BYD, Tencent, Xiaomi, Huawei and Unitree Robotics, Xi is reported to have said, “It is time for private enterprises and private entrepreneurs to show their talents” and that his government “must resolutely remove various obstacles” faced by private firms.

According to China’s official media, Xi seemed to acknowledge that recent regulatory changes were key obstacles and he said they were “temporary rather than long term, and can be overcome rather than unsolvable.” With this language, Xi may have been trying to refute the view held by some that recent regulatory obstacles faced by entrepreneurs had an ideological origin.

Of course, talk is cheap. We now need to see if Xi has persuaded a significant number of entrepreneurs that it is again a good time to hire and invest in their own businesses. Xi will also have to deliver on his pledge to create a more entrepreneur-friendly regulatory environment. The next opportunity for him to demonstrate further pragmatism is in March, during the annual session of China’s legislature.

Will It Work?

When Xi does finally course correct in a pragmatic way, it is likely that Chinese entrepreneurs and consumers will bounce back. They have, historically, been tremendously resilient. That resilience will be supported by continued accommodative monetary policy and high savings. Family bank balances have increased 86% from the start of 2020, as Chinese households were in savings mode during the country’s zero-COVID policy. The net increase in household bank accounts is equal to US$9.8 trillion, which is more than double the size of Japan’s 2023 GDP and greater than the value of China’s pre-COVID 2019 retail sales. This could be significant fuel for a consumer spending rebound.1

When Xi does put the domestic economy back on track, that will outweigh any headwinds from tensions in the U.S.-China relationship.

Andy Rothman

Andy Rothman is a China strategist and founder of Sinology LLC

Sources: 1 CEIC; 2 People’s Daily

Definitions: * Net exports is the value of a country's total exports minus the value of its total imports. It is a measure used to calculate a country's gross domestic product (GDP). ** Nominal GDP is the total value of all goods and services produced in an economy whereas real GDP is nominal GDP adjusted for inflation.