China’s Macro Prospects: Five Key Questions

Five topics to think about the policy and macro environment for the next few quarters.

Manufacturing has completely recovered from COVID. For example, over the first half of this year, the two-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of industrial value-added was 7%, faster than the 6% year-over-year (YoY) pace during the first half of 2019, before the pandemic.

Just published macro data for the second quarter revealed few surprises, as the Chinese economy continued to recover from COVID-19. I am now focused on what lies ahead, and in this issue of Sinology I discuss five topics that will help investors think about the policy and macro environment for the next several quarters.

I expect the U.S.-China political relationship to remain uneasy, at least through next November’s Congressional mid-term elections, and while this may weigh on investor sentiment, those political tensions should have little impact on the Chinese economy. Regulatory changes in China are being driven by concerns which are similar to those being addressed in Washington, London, Brussels other capitals around the world, and although they create short-term volatility, they are likely to be good for the long-term health of sectors as diverse as pharma, education and internet platforms. There is no evidence that the Chinese government has become less supportive of privately owned companies.

Manufacturing has completely recovered from the pandemic, but periodic, small COVID outbreaks have left many Chinese consumers wary of spending on services that require gathering in confined spaces. I expect the services sector to gradually recover as the share of Chinese consumers who have been vaccinated rises. The residential property market remains healthy, with limited leverage for buyers.

I expect some fine-tuning of monetary policy in the second half of the year, including a minor uptick in the pace of credit growth, but I believe the central bank when they say they “won’t flood the economy with stimulus.” De-risking of the financial system should continue.

What is the direction of U.S. – China relations?

The Biden administration has used less politically charged rhetoric, compared to the previous administration, in talking about China, but has continued to pursue an approach that can be best described as containment, albeit without specifically calling it containment. A senior White House official recently declared that “the period that was broadly described as engagement [with China] has come to an end,” and in the future, “the dominant paradigm is going to be competition.”

The Biden administration has yet to even reverse some of the own goals scored by the previous administration, including shuttering two programs— the Peace Corps in China and the U.S.-China Fulbright Program—which promoted people-to-people exchanges and provided thousands of Americans with an opportunity to learn more about China.

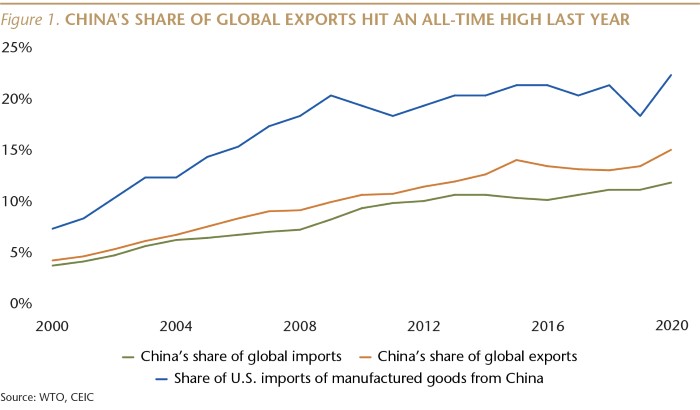

The previous administration’s punitive tariffs on Chinese imports have also not been withdrawn, despite clear evidence that they have been costly for American consumers and have not put pressure on China’s exports, or on policy-makers in Beijing.

Economists at the Fed, Princeton and Columbia universities collaborated on a study which found that “The full incidence of the tariffs falls on domestic consumers . . . with no impact so far on the prices received by foreign exporters.” Economists at the Fed also concluded that “The tariffs have not boosted manufacturing employment or output” in the U.S.

Despite the tariffs and political tensions, the share of manufactured goods imports coming into the U.S. from China last year returned to the historical high of 22%. In addition, China’s share of global exports hit an all-time high of almost 15% last year.

Yet, the tariffs remain in place.

(For a discussion about the benefits to the U.S. economy of engaging with China, please see the March 29, 2021 Sinology, “Dear President Biden”).

I expect the bilateral political relationship to remain uneasy, at least through next November’s Congressional mid-term elections. But, while these political tensions may weigh on investor sentiment, they are likely to continue to have little impact on the Chinese economy, which is fueled primarily by domestic demand, not exports. Last year was the ninth consecutive year in which the services and consumption (tertiary) part of China’s GDP was larger than the manufacturing and construction (secondary) part, as rebalancing continued despite the pandemic. Chinese consumer spending, as well as investment in their home equities markets, should remain well insulated from tensions with Washington.

What is the direction of China’s regulatory environment?

I believe there are three factors which have influenced recent regulatory changes in China.

The first factor concerns the relationship between a few private companies and the Chinese government. Since allowing the re-establishment of privately owned firms in the 1980s, the government has made clear that while entrepreneurs are free to become rich and famous, they cannot use their wealth and fame to challenge the government on political and governance issues. Unsurprisingly, the government recently intervened after two well-known companies questioned or ignored the advice of regulators. This is one of the many reasons we advocate for an active, rather than a passive, approach to investing in Chinese equities.

The second factor is the Chinese government’s concern for data security and privacy, along with a desire to promote competition, protect consumer and small business interests, and tackle economic inequality issues. These considerations are very similar to the discussions taking place in Washington, London, Brussels and other capitals around the world regarding the best ways to regulate the tech industry, protect consumers and reduce inequality.

These regulatory changes in China, which have to date covered sectors as diverse as pharmaceuticals, online gaming, education, internet platforms and real estate, are likely to be good for the long-term health of these industries and China’s economy. But, because the Chinese government has the ability to act quickly, and often does not clearly articulate its policy objectives, these changes can create short-term volatility in market sentiment.

The third factor is concern by the Chinese government about the rising tensions in the political relationship with the U.S., and the direction of President Biden’s China policy. This may be leading the Chinese government to take steps to reduce the degree of interconnectivity between the two economies, including Chinese company participation in U.S. capital markets.

It is possible that the Chinese government is anticipating that American regulators may in the coming years force Chinese companies to delist from U.S. markets, and Beijing may want to block more companies from joining a club where they are no longer welcome. It is also possible that Beijing may encourage Chinese companies already listed in the U.S. to switch to exchanges in Hong Kong, Shanghai or Shenzhen.

It is not clear how far the Chinese government wants to move in this direction, and recent rhetoric may largely be a signal to the Biden administration rather than an indication of a major change in Chinese regulatory policy.

Given the liberalization of the Chinese capital markets, we are confident that despite the recent regulatory actions, which could prompt or accelerate the decision for Chinese companies listed on U.S. exchanges to seek secondary listings on exchanges in Hong Kong or mainland China, investors such as Matthews Asia will still be able to access the opportunities presented by these businesses on behalf of the strategies we manage for our clients.

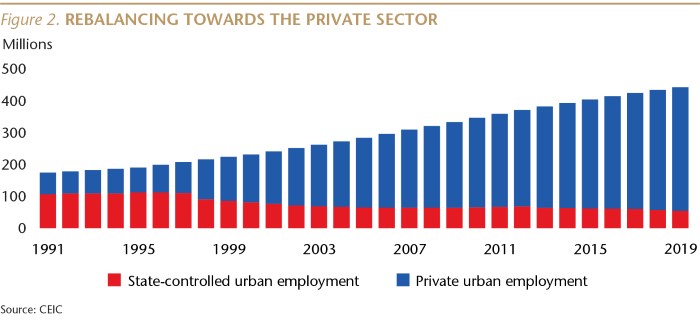

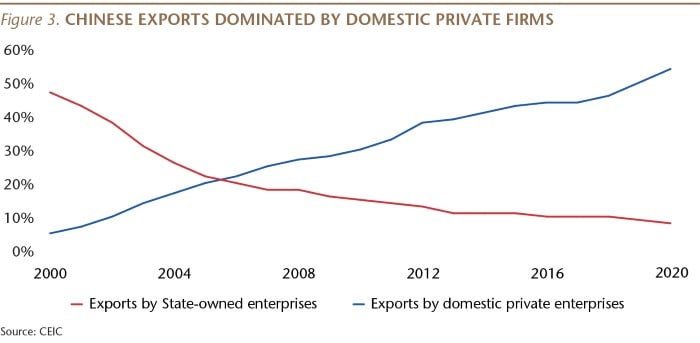

I’d also like to emphasize that, in my view, there is no evidence that the Chinese government has become less supportive of privately owned companies.

It is clear that private firms are the engine of China’s growth and job creation. Almost 90% of urban employment is in private companies, and private firms also account for the majority of China’s exports.

Privately owned companies are China’s most innovative firms, and the government’s economic growth plans are based on innovation. We also note that the two largest, publicly listed Chinese companies, by market cap, are privately owned. Privately owned firms also account for about 80% of companies listed on China’s science and technology board, its version of NASDAQ.

In the financial sector, I believe the government is encouraging limited competition. In January, a senior Chinese financial sector regulator stated that “the private economy is an indispensable driving force of our country.” He added that, “financial regulatory authorities have always supported the development of the private economy.”

The regulator noted that “internet platform companies such as Ant Group . . . have played an innovative role in developing financial technology, and improving the efficiency and inclusiveness of financial services.”

Has China's consumer sector recovered fully from COVID?

Manufacturing has completely recovered from COVID. For example, over the first half of this year, the two-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of industrial value-added was 7%, faster than the 6% year-over-year (YoY) pace during the first half of 2019, before the pandemic.

However, consumption of goods and services is the largest part of China’s economy, and that has yet to fully recover. In the first half of the year, the two-year CAGR of household consumption was 5.4% compared to 7.5% YoY in 1H19.

Spending on some consumer goods has rebounded nicely. Sales of food, liquor and tobacco actually rose faster in the first half than during the same period in pre-COVID 2019.

But, spending on services has struggled to rebound. The two-year CAGR of household spending on education, cultural, entertainment, medical and transport services all remain well below their pre-pandemic rates.

The problem is not lack of income. Per capita disposable income rose 15.4% in the first half compared to the same period in pre-pandemic 2019, with a two-year CAGR of 7.4%.

The problem, in my view, is that periodic, small COVID outbreaks have resulted in aggressive, localized lockdowns, which have left many Chinese consumers wary of spending on services that require gathering in confined spaces.

To be sure, COVID remains largely under control in China. As of July 14, there were only 506 people in Chinese hospitals with COVID, compared to over 15,000 in the U.S. Since the start of the year, only two people in China have died as a result of COVID, compared to almost 260,000 in the U.S.

But during months when there has been an increase in COVID cases, retail sales have been weaker. I expect spending on services to gradually recover as the share of Chinese consumers who have been vaccinated rises. (China had administered 100 vaccine doses per 100 people as of July 13, up from only 26 doses as of May 13. During that period, the U.S. went from 80 doses per 100 people to 100, and the UK went from 82 to 119 doses.*) The Chinese government aims to fully vaccinate all of the eligible population by the end of the year.

Inflation is unlikely to be an obstacle to improved consumer spending. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose by only 1.1% YoY in 2Q21, while core CPI rose 0.8%.

*For vaccines that require multiple doses, each individual dose is counted. As the same person may receive more than one dose, the number of doses per 100 people can be higher than 100. Source: Our World In Data

How has the property market weathered COVID?

New home sales rose 19.5% in the first half compared to pre-pandemic 1H19, on a square meter basis. Sharp increases in home prices have been limited to a small number of cities, and overall, prices have risen in line with income.

Over the 10 years through 2019, prior to the pandemic, new home prices rose at an average annual pace of 7.7%, while nominal urban income rose at an average rate of 9.5%. The pandemic interrupted this balance last year, with new home prices up 7.5% YoY in 2020, compared to a 3.5% YoY increase in nominal urban income, but that was a temporary aberration. In the first half of this year, new home prices rose 9.7% YoY, while nominal urban income rose 11.4%.

China’s housing market is not generating the kind of financial system risks that developed in the U.S. during the decade prior to the Global Financial Crisis, in part because China’s regulators have learned from our mistakes. In fact, because homebuyers are required to use a lot of cash and because banks have not been permitted to make irresponsible loans, mortgages may be among the safest of bank assets in China.

Chinese homebuyers who use a mortgage must put down at least 20% cash for a primary residence (and much more for an investment property), in sharp contrast to the 2% median cash down payment in the U.S. in 2006.

It is also worth noting that Chinese banks have not been permitted to engage in the “financial engineering” that caused the U.S. crisis. For example, nearly one-quarter of all mortgages originated in the first half of 2005 in the U.S. were interest-only loans. Those do not exist in China.

There is very little mortgage securitization in China, and most banks hold mortgages through maturity, so they have a clear incentive to avoid lending to risky borrowers.

And the government has been continually fine-tuning its policies to limit property market speculation and promote the construction of lower-cost housing. Recent regulations have also limited bank exposure to the property sector.

China does face a serious property problem—but it is a social and political problem. In larger cities, many residents are priced out of the market and may never be able to afford to own a home. This problem—shared by cities such as San Francisco, New York and London—is a long-term challenge, and it’s one with consequences that are very different from a housing bubble.

What will monetary policy look like in the second half?

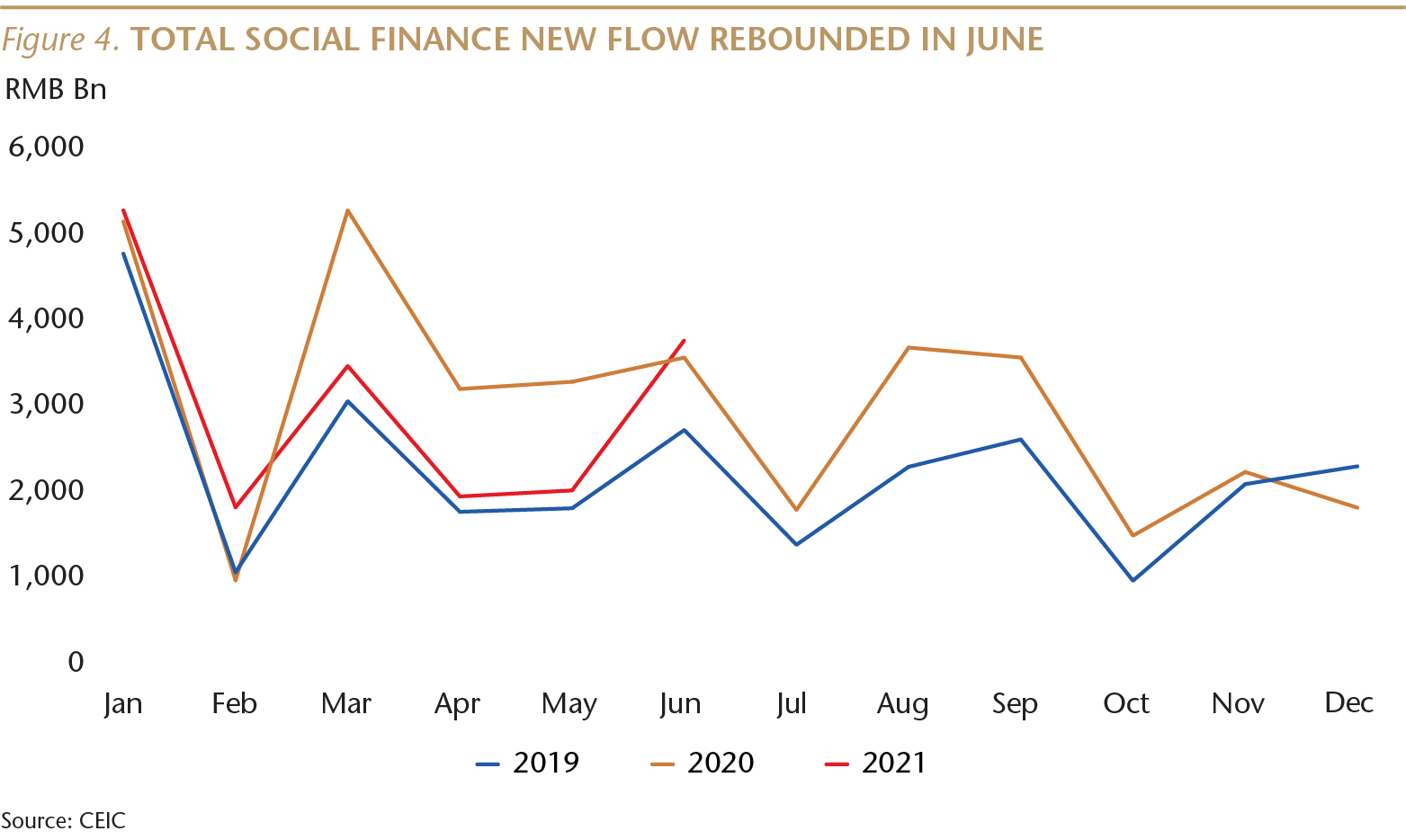

Following a modest stimulus in response to COVID, the central bank has been normalizing the pace of credit growth since last fall. I expect some fine-tuning in the second half of the year, including a minor uptick in the pace of credit growth, but I believe the central bank when they say they “won’t flood the economy with stimulus.”

The fine-tuning may have begun in June, when the new flow of Total Social Finance (TSF, the broadest measure of credit in China) rebounded to a level above that during June of last year. The central bank’s early July announcement that it will cut the required reserve ratio (RRR) for financial institutions is another signal of plans for modest easing.

At the same time, I expect the central bank to continue with its efforts to reduce risks in the financial system. June was the 37th consecutive month in which shadow (off-balance-sheet) loans outstanding declined YoY.

Concluding Comments

The macro picture looks healthy for the coming quarters, including an expectation of a fuller recovery in consumer spending on services. There are two key risks. The first is the risk that the central bank fails to provide enough credit and liquidity to support the final legs of recovery from COVID, but I think this is a modest risk, especially given last month’s uptick in new credit flow.

The second risk is with the political and regulatory environment. Foreign investor sentiment may suffer under the weight of rising political tensions between Washington and Beijing, but this is unlikely to disrupt spending by Chinese consumers, or their investments in their home equities markets. More regulatory changes are expected, especially in sectors which are data-rich, and these have the potential to create near-term volatility if not communicated clearly. In the long run, these regulatory changes are likely to create a supportive environment for quality companies.

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist

Matthews Asia